Daniel Fitzpatrick of West Brighton took his own life in 2016 at the age of 13. (Photo courtesy of the Fitzpatrick family)

STATEN ISLAND, N.Y. — A swimming pool in the Fitzpatrick family’s West Brighton back yard serves as a constant reminder of what they lost when their son took his own life in 2016.

Danny Fitzpatrick died on Aug. 11 of that year at the age of 13. His mother Maureen told the Advance the family will never be the same.

“She [Danny’s sister Kristen, 19] was out in the yard the other day with her friend, and I think this is the first time I’ve seen her use the pool since my son passed away,” Mrs. Fitzpatrick said.

The loss the Fitzpatricks experienced is happening to families across the nation.

(Staten Island Advance/ Paul Liotta)

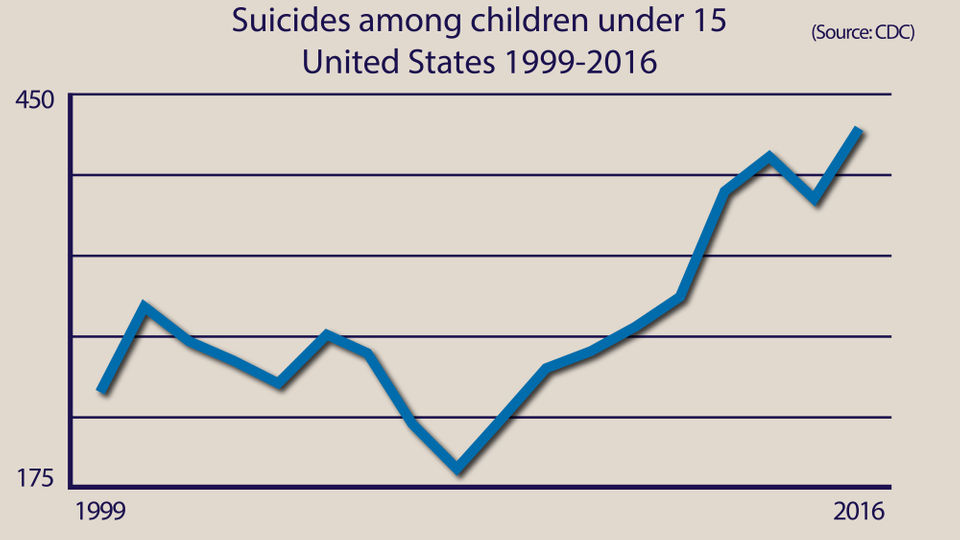

From 1999-2016 the total number of suicides for children under 15 in the nation went from 244 to 443, and the rate per 100,000 for those children taking their own lives roughly doubled, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

“It’s not the answer, because the pain doesn’t go away, it just gets transferred to other people,” Mrs. Fitzpatrick said.

The Fitzpatricks believe bullying to be the cause of their son’s suicide, and filed a lawsuit against Danny’s school, alleging he was “the victim of daily abuse, harassment and torment by classmates… for years leading up to his death.”

Left to right Felicia Garcia, Amanda Cummings, and Danny Fitzpatrick.

Their claim was reminiscent of two 15-year-old girls from Staten Island, who died in 2012 from apparent suicides, amid allegations they fell victim to bullying.

Amanda Cummings died in January of that year after she jumped in front of a bus on Dec. 27, 2011 at the intersection of Hunter Avenue and Hylan Boulevard.

Her family maintained Amanda dealt with bullying, but police at the time said they found no evidence it played a role in her death.

Felicia Garcia completed suicide in October of that year when she leapt in front of an oncoming train at the Huguenot Station of the Staten Island Railway.

Friends took to social media immediately after her death to rail against the bullying Garcia faced, according to Advance reports.

(Staten Island Advance/ Paul Liotta)

However, mental health experts say an exact cause for the trend is hard to pin down.

Libby Traynor, the chief clinical officer for the Staten Island Mental Health Society, described finding the cause as the “million dollar question.”

“It’s so many factors, and I think it’s on a much larger scale than what’s here on Staten Island,” she said.

“Nationally we’re seeing these trends as well, so I don’t think that we are different than other communities that are struggling with this.”

Referrals to the Staten Island Mental Health Society for children struggling with suicidal ideations, gestures, or attempts nearly doubled from 2016 to 2017, according to the organization’s President and CEO Fern Zagor.

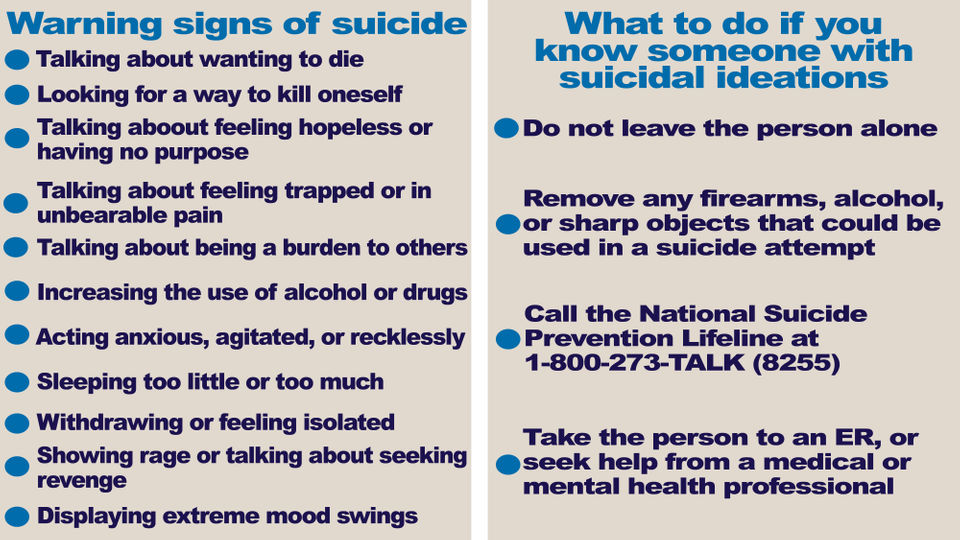

Traynor described suicidal ideations as thinking about a plan of doing harm, a gesture as an action to put that plan into motion, and an attempt as performing an action to intentionally take your own life.

In the past year, hospitals referred 150 children to the Staten Island Mental Health Society for this issue — 40 of which made serious attempts on their life — Traynor said.

D.A.N.N.Y. Inc. presents “Dare to Care Day” a charity softball/carnival a bullying awareness event at Mid-Island Babe Ruth League, Travis. (Staten Island Advance/ Jan Somma-Hammel)

Those attempts — often committed by children who were victims of trauma — have also become more serious in recent years, she said.

“In years past an attempter may have taken a small handful of pills — six, eight pills of either prescription or over the counter medication — now we see kids who have come in and taken the entire bottle — the value size, 90, 100 pills,” she said.

“These attempts are becoming more lethal, more acute, and at younger ages.”

Zagor said that most of the children — as young as six or seven — her organization works with know what they’re doing.

“These are children who are so anxious, so depressed, so demoralized, that they see as their best way out at that time is to die,” she said.

Those emotions are some of the causes both women attribute to the rising suicide rate.

Zagor noted an uptick in suicide referrals to her organization at the start of the school year, particularly around the first report card, when the children find themselves under the most pressure.

Daniel Fitzpatrick talks about his son Danny as attorney Sanford Rubenstein looks on during a press conference Thursday, Jan. 26, 2017 at the offices of Rubenstein & Rynecki in Brooklyn announcing a wrongful death lawsuit in the suicide death of Danny Fitzpatrick, 13. (Staten Island Advance/ Bill Lyons)

The common challenges of growing up that everyone experiences are still in place, but they’ve been exacerbated by modern society and technology, Traynor said.

Children’s connection to social media can also leave them without reprieve, if they are being bullied at school, Zagor said.

“Kids that we talk to are on their phones all the time, and the communication is constant,” she said. “We as adults don’t always know what’s in that communication, and we certainly have limited to no control over it.”

Danny Fitzpatrick’s parents said they don’t believe cyber bullying led to their son’s decision — they only have one computer in their home, and were unaware of their son having social media accounts.

His father, Daniel, believes technology has played a role in desensitizing society, which contributed to the bullying he says his son received.

However, Traynor sees technology as a “double-edged sword” that can contribute to a society more open to talking about mental health.

“I think this generation of kids are more open to talking about everything,” she said.

“Not that stigma’s gone — it’s definitely a barrier, and it’s still there, and we still have work to do around it, but this is a generation that does reach out and does look for information.”

She recalled one referral in which a child demanded help, telling parents and doctors “I’m not leaving until you adults figure it out.”

“I was just astounded, and that was in quotes ‘I need help. Figure it out,'” Traynor said. “I don’t think five, 10, 15 years ago that a kid would have that type of presence.”

Zagor and Traynor see outreach and education, as the best ways to fight the growing number of child suicides.

Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza at a visit to Susan E. Wagner High School in Sea View (Staten Island Advance/ Paul Liotta)

The New York City Department of Education (DOE) offers three different training programs for school staff to learn how to identify, and help children dealing with psychological distress, according to DOE spokeswoman Miranda Barbot.

As of Aug. 1, approximately 60,000 school staffers participated in at least one of the training programs that the city spends $47 million a year on.

“We remain committed to providing safe, supportive and inclusive learning environments for all students and staff, and in partnership with ThriveNYC, we ensure mental health resources are available to every school,” Barbot said.

ThriveNYC is the city’s overall mental health initiative.

Any adult in a child’s life who notices warning signs like changes in behavior or sleep needs to get that child help, Zagor said.

“Any talk from any child about wanting to die has to be taken seriously,” she said. “Often times we think that ‘oh they’re just saying, I had a bad day today, I wish I was dead’ well you can’t slough that off.”

Being open to talking about the specific subject of suicide, and more broadly about mental health can help prevent suicidal behavior, Traynor said.

Even with adults doing what they can to help, she doesn’t see a change in the trend direction of child suicide coming.

“I don’t see any stop to it,” Traynor said. “I think that we are trending with more and more referrals this year versus last year, and the year prior. Within what I’ve described; the number of referrals, the acuity, the suicidal behaviors are all trending up.”